Timing and context is really important when assessing policies such as the First Home Loan Deposit Scheme, which copped a bagging by Peter Van Onselen in The Australian yesterday. Pete and I go back years, both working at Sky News and he’s a really smart guy — a Professor of politics and public policy at the Uni of WA.

He's also not a great fan of Scott Morrison as regular readers and viewers of his work on TEN might have noticed.

In a nutshell, this is why he thinks the latest version of this scheme to get first homebuyers into a house on the cheap is bad policy, which he lambasts Labor for supporting.

This is why he hates the policy:

All of this is bound to create mortgage stress and it’s a policy that Peter thinks should be pulled back, not pumped up for political purposes.

This is a pretty impressive list of reasons why the scheme should be canned or pulled back rather than ramped up but some context needs to be understood about this scheme.

It actually kicked off in January 2020, before the Coronavirus lockdown and stock market crash of February/March 2020 and 2019 was not a great year for real estate, after Bill Shorten threatened changes to negative gearing and the capital gain discount.

This was the headline of a story on livewiremarkets.com by Angela Ashton: 'Sydney & Melbourne house prices lead the race downwards in 2019.'

This was not a boom time for property, as Ashton’s next observation points out: “At this point, we continue to reiterate that we are not anticipating an economy-wide collapse in house prices, which would likely require an increase in unemployment and lending rates. In fact, boosted sentiment from the surprise federal election result and recent changes to monetary policy and other settings have placed a firm floor under the housing market.”

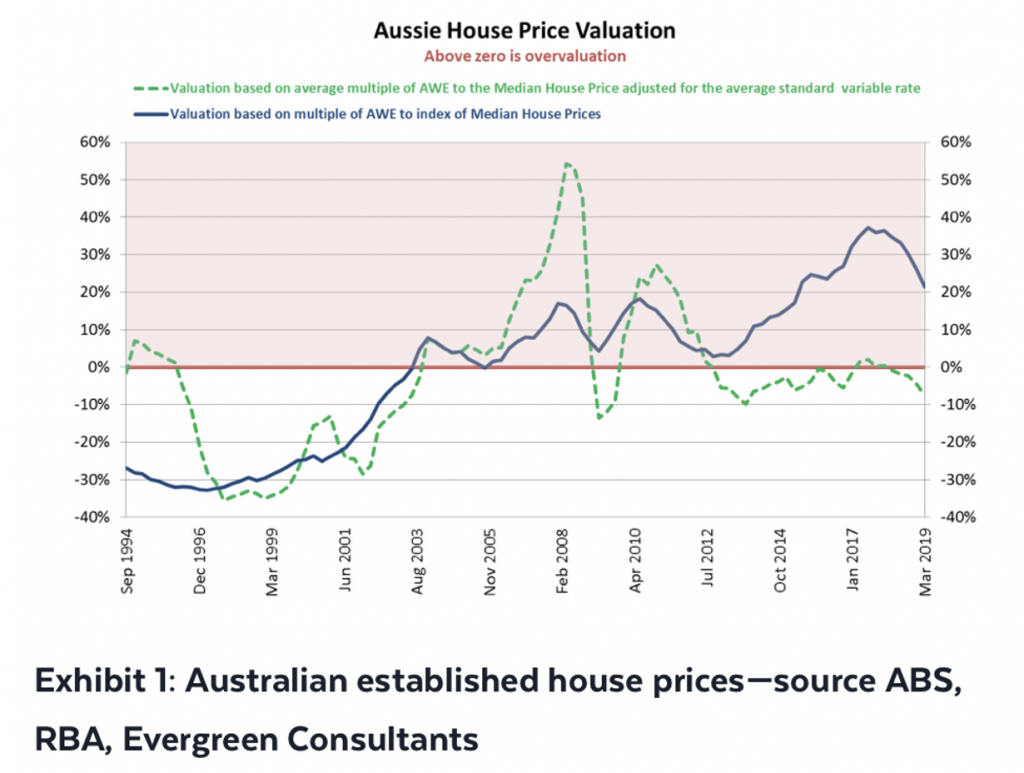

And this chart below shows it graphically.

Then along came the pandemic and the threat of a Great Depression and government policy went into “do anything” mode to keep people in jobs. So this policy promised jobs, homes and turning tenants into homeowners — what was not to like about that at the time?

The policy has always rested on the banks lending sensibly, and there is a buffer supposedly on all loans, which estimates if a borrower could stand a 3% rise in interest rates.

On the taxpayer issue of having to bail out borrowers under the scheme, well taxpayers receive a lot of money from homebuyers with stamp duty and via taxes on developers. And the economy does benefit from the jobs created via a healthy building and construction sector.

At the time this policy had more merit, as it stopped a lot of young borrowers from having to pay mortgage insurance that has been a very expensive slug in the past. However, with interest rates set to rise and prices set to fall from historically high levels, putting this policy on steroids is more explainable in terms of the upcoming election, rather than it being an economic necessity.

If the young are kept out of the housing market for a couple of years, they will undoubtedly be buying at lower prices, albeit with higher interest rates, but at least there is less likelihood of the mortgage stress of rising repayments as house prices fall and negative equity becomes a concern.

Of course, lots of us have lived through these challenges — those who borrowed in the 1980s and saw interest rates hit 18% will attest to this — and our homes have become more valuable. However, it’s not an ideal policy given what lies ahead. But that's politics.