Employment fell by -30,600 in April. It’s up 5.1% from April last year reflecting the base effect of the plunge in jobs seen last April. Employment is up 0.3% from its pre-coronavirus level in February last year. While employment fell, the compositional mix was less negative with part time jobs down by 64,400 but full time jobs up by 33,800. Unemployment fell to 5.5% from 5.6%, despite the fall in employment because labour force participation fell back to 66% from a record 66.3% in March.

The 30,600 decline in employment may have been impacted by the end of JobKeeper at the end of March, as the survey reference period for the April jobs data was from 4-17 April. However, the impact looks to have been minimal, with the ABS noting that its analysis “did not identify a clear aggregate impact from the end of JobKeeper”. This is consistent with data showing a decline in people on unemployment benefits in April and Government analysis of payroll data showing that only 16,000 to 40,000 people on the wage subsidy had lost their jobs up till April 11. This is minor compared to concerns that many jobs would be lost as one million jobs were still on JobKeeper prior to its ending.

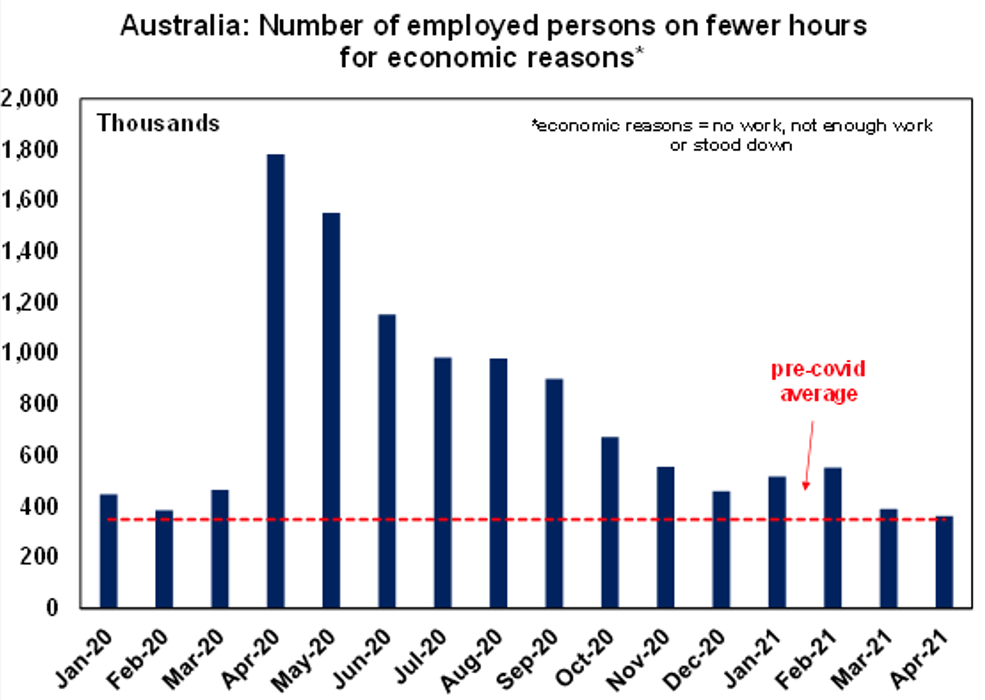

One indicator that had been pointing to a minimal impact from the ending of JobKeeper was the number of employed people working fewer hours for economic reasons as this was a good guide to the number of jobs that were vulnerable. But as can been seen in the next chart, this was around its pre-Covid average in March and remained there in April, which would suggest little in the way of JobKeeper layoffs still to come.

Correction after two strong months

More likely though is that the 30,600 decline owes to normal month-to-month volatility after two far stronger-than-expected months for jobs growth (with employment up by an upwardly revised 77,000 in March and 84,000 in February). Note also that the trend in unemployment remains down and its usually a better indicator of the state of the jobs market than month to month employment swings, and the rise in full time jobs is a positive sign.

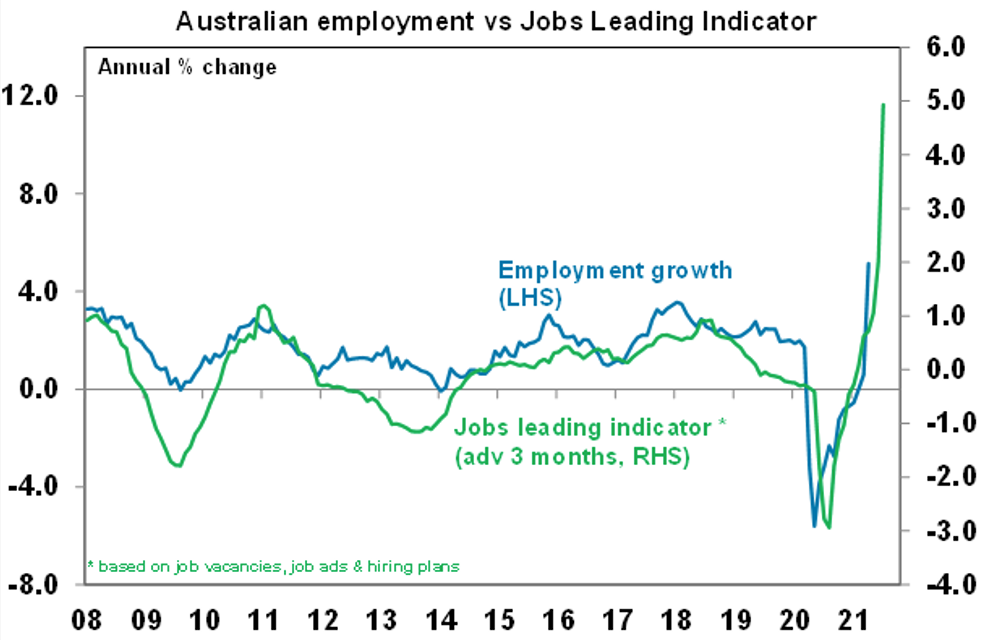

Our Jobs Leading Indicator

Looking more broadly, our Jobs Leading Indicator suggests that the fall in employment in April is just a temporary setback with strong jobs growth likely to resume in the months ahead reflecting record or near record levels for job vacancies, job advertisements (across various indicators) and business hiring plans. Bear in mind though that this is partly catch up to the slump in jobs seen in April-May last year. The high level of job vacancies would suggest that most of those who have lost their jobs as a result of the end of JobKeeper should be able to find new jobs.

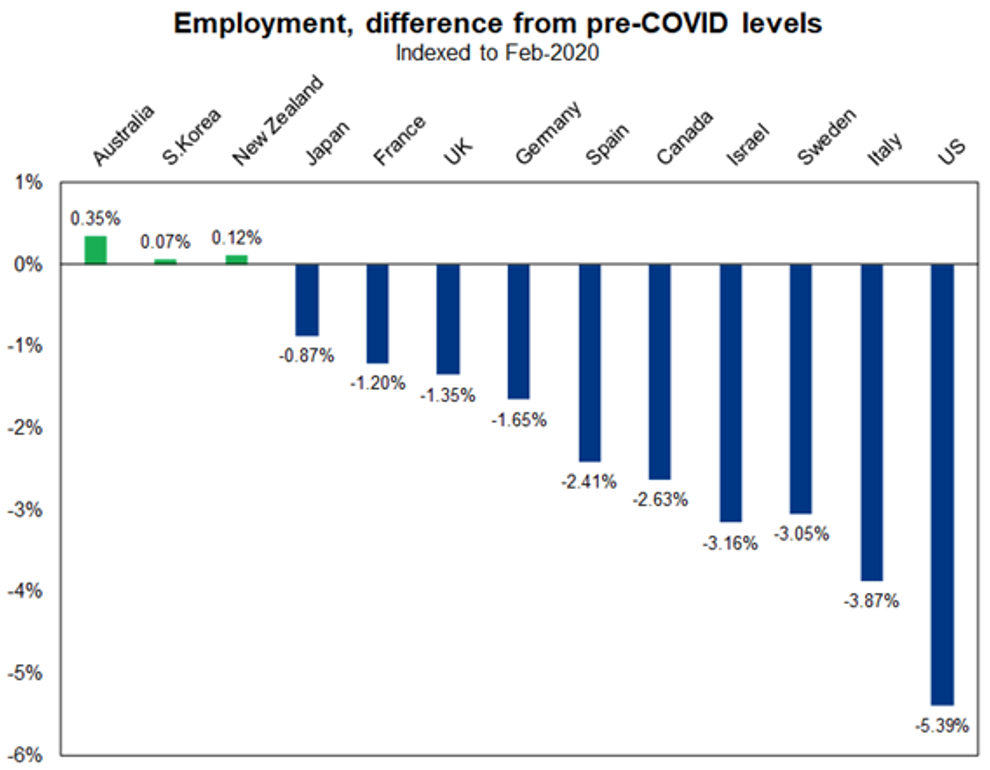

As can be seen in the next chart, the Australian labour market has recovered far quicker than most other comparable countries reflecting better management of the virus and better government support programs.

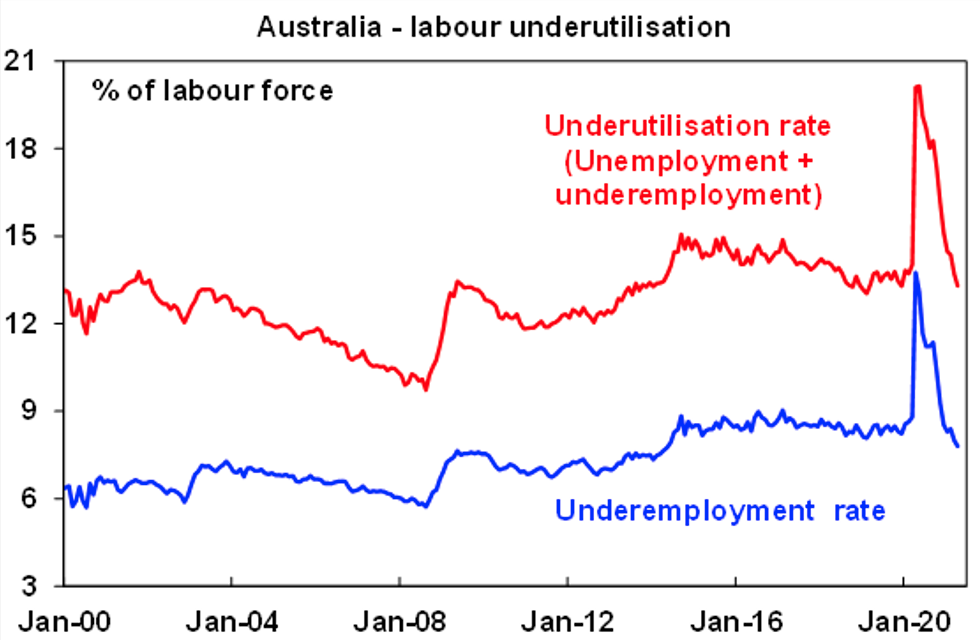

Implications for the RBA

The obvious question remains whether the strong underlying jobs market and the decline in unemployment will bring forward RBA rate hikes. While unemployment is falling rapidly and labour underutilisation at 13.3% is now below it pre coronavirus level, we remain of the view that there is a long way to go to full employment. Based on the pre coronavirus experience the NAIRU (or non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment) is likely to be 4% or just below for traditional unemployment and 6% or so for underemployment or around 10% or just below for labour underutilisation. So with underutilisation at 13.3% we still have a fair way to go to get to full employment. As such, we likely also still have a fair way to go to get to the RBA’s requirement for wages growth to be “sustainably above 3%”. While some have interpreted March quarter’s stronger than expected 0.6% quarterly rise in wages growth as a sign that wages growth is picking up we think there is little evidence to support that as the March quarter rise was boosted by the phased implementation of last year’s minimum wage rise and an ongoing return to pre coronavirus wages for those who saw pay cuts last year. We think the first rate hike will come earlier than the RBA’s “2024 at the earliest” but it’s still going to be not until 2023. In the mean time the stronger jobs market recovery is consistent with the RBA announcing in July that it will stick with the April 2024 bond for its three year bond yield target and that it will taper its weekly bond buying to $2.5bn a week from $5bn a week from September.