The war in the Middle East has to be worrying for many stock players and super members who’ve had a good year. The question is this: how worried should you be about a possible escalation of the conflict? Israel looks determined to seek out its enemies who are committed to their destruction. Iran is the wild card that could turn this tragedy into a global nightmare.

Of course, that’s the worst-case scenario, but it’s worthwhile to look at how the stock market reacts to serious geopolitical events. Before looking at the market reaction in the short- and longer-term, let’s look at the key forces operating now that could influence where stocks go over the next few months.

Sure, the Middle East remains a potential worrying negative but against this the huge stimulus from Beijing combined with US interest rate cuts (where the threat of recession is low) are what we call tailwinds for lifting share prices.

Locally, we’re expecting rate cuts by February. When that looks more certain, it will help our market play catch up with the US market. Over the past year, the US-based S&P 500 index is up 32.65%, helped by a better assault on inflation. Meanwhile, our S&P/ASX 200 index was up only 17.72%, so there’s room for gains, provided the Middle East problem doesn’t get out of hand.

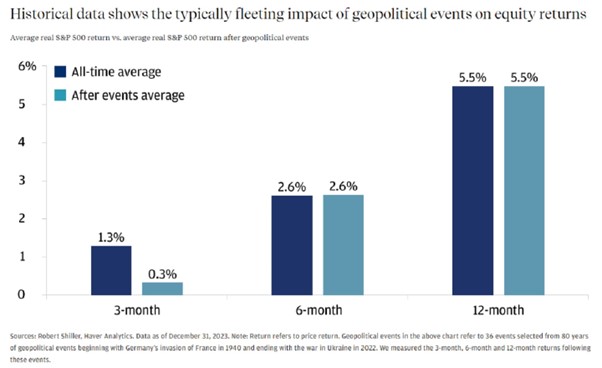

For those non-history buffs, when it comes to stock markets faced with geopolitical crises, research from J.P.Morgan has found the following: “We conclude that in the three months after an event, the market underperforms, on average, but – this is key – six-month and 12-month subsequent returns are identical. When you consider the average equity investor experience, it’s as though the event never happened!” That’s my exclamation mark and I think it’s deserved.

This chart shows that in a non-geopolitical three-month period, the average gain from stocks is 1.3%. But when things get scary, the market reacts negatively. However, note how after six months and 12 months the market gains are unaffected. (That’s why the light and dark blue bars are about the same.)

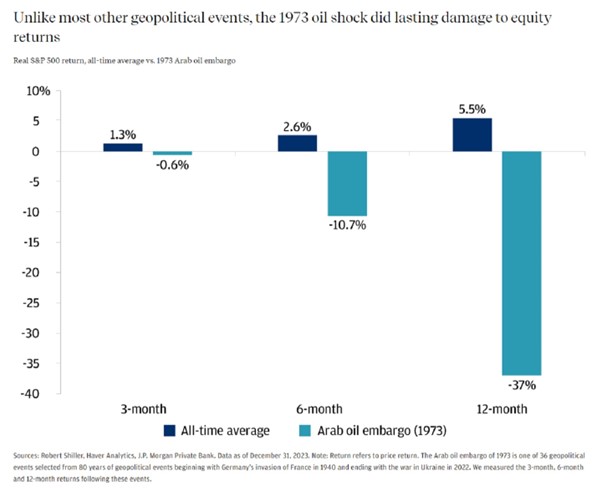

OK, on an average basis, this Middle East war should be seen as a short-term problem for stock market returns. But what if this event is like 1973 when OPEC conspired to spike prices, which spread inflation and ended in a global recession?

The chart below shows if the price of oil spikes big time, then we might have a “Houston, we have a problem” situation.

Iran only supplies 3% of the global market and it could force oil and petrol prices up, but it’s not a threat to overall oil prices when compared to the oil shock of the 1970s.

As J.P.Morgan explained: “…high oil prices essentially stopped the economy from operating efficiently in the 1970s. In contrast, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine shocked global energy markets in 2022, additional oil supply rapidly came on stream. As a result, the economic and market impact of the recent shock was less severe and sustained than its 1970s counterpart.”

And for that you can thank Uncle Sam! “The main structural difference between the two episodes relates to U.S. oil production,” the JPM researchers revealed. “In the 1970s, the United States was producing as much oil as it could with the technology available at the time. Thus, the United States relied heavily on oil produced in the Middle East. Today, by contrast, production is flexible, and U.S. oil is generally plentiful, thanks in large part to the boom in shale fracking.”

On this subject, Reuters looked at the Russia and Ukraine war and used the work of Glenview Trust Co's Chief Investment Officer Bill Stone, who examined market moves around past geopolitical crises for clues as to what investors might expect.

Reuters says Stone looked at 29 different geopolitical crises, starting with WWII. He found that on average, stocks were higher three months after a geopolitical shock, and following 66% of events, they were higher after only one month. "The odds that stocks will be higher increases as time passes after the event. In addition, stocks sometimes jump sharply after a crisis, so getting out of the market could have significant opportunity costs," Stone cautioned.

Of course, there have been outliers in the form of more severe spillovers into the economy and financial markets, but I have noticed that other market issues were also operating at the same time.

For example, September 11 coincided with the dotcom crash, and the Gulf War in 1990-91 happened as a global recession happened.

So, while investors should be prepared for additional volatility, history does seem to suggest that stock declines associated with geopolitical fears are generally "a temporary setback” and consequently it’s often an opportunity to buy stocks at lower prices.

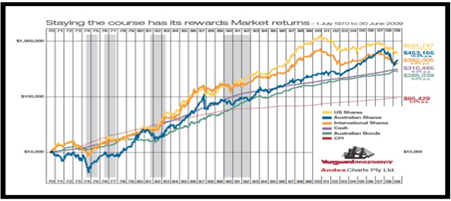

One last point I have to make. It involves my favourite stock market chart.

The graph below shows how $10,000 invested in the overall Aussie stock market with dividends reinvested grew into $453,166 between 1970 and 2009, which was after the market crashed 50% in 2008 with the GFC.

The blue line shows how many crashes and big corrections happened over that time, but the stock market kept climbing and climbing.

The bottom line is that it’s not worthwhile getting too worried about most geopolitical crises because eventually the world’s economies adjust and grow, which then helps stock prices rebound.

As the old song goes: “Don’t worry, be happy.”