The World Bank estimates almost 93% of countries will face economic contraction on a per head basis in 2020 as a result of this Coronavirus pandemic. It’s a crisis that has impacted businesses, with a global halt in economic activity. However while some businesses are being disrupted, others will undoubtedly thrive in the post-crisis recovery.

It has become more difficult for those investors who seek regular income streams with some capital stability, Interest rates have been pushed down further and the earnings outlook on some companies is unclear. The post-inflation returns to investors in term deposits is now negative.

In times of uncertainty, we tend to shift to quality or move further up the capital stack to achieve capital stability and deliver attractive risk-adjusted returns.

What is real estate debt?

Real estate debt is where the lender provides capital to finance the purchase of a property asset, or the development or redevelopment of a property. In Freehill’s case, the lender is the fund. In return for providing the capital, the fund (and ultimately investors) receives interest on the loan, which is paid either monthly, quarterly, or capitalised and paid at the end of the loan term.

How the value of an asset (which is the security for the loan) is determined varies by asset type. If the loan is simply financing the acquisition of land, it is secured against the current value of that land. However a construction or redevelopment loan is typically secured against the end value of the project. The end value includes improvements that the loan is being used to finance.

For loans financing residential development, land acquisition or construction, the weighted loan-to-value ratio (LVR) for senior secured first mortgages (which is our area of focus) tends to be between 40% to 60% and the gross interest costs to borrowers are between 8% to12% a year.

In instances where the purchase of a commercial property (such as an office building or retail centre) is being funded, the loan is secured against the market value of the asset and the interest is paid with the rent of the underlying asset. Banks continue to be an active lender to commercial property, so usually non-banks finance commercial assets where the loan-to-value ratios are stretched (this means the ratio is more than 65%) or when an asset is being repositioned.

Drivers behind the growing investment in real estate debt

Historically, most real estate developers would approach a traditional bank to obtain funding for their projects, which has led to the banks holding a dominant share of the sector. This was at the time when there were fewer options to source finance through non-bank lenders.

Since the GFC, real estate debt has grown in importance as an asset class. The growth (which continues today) can be attributed to a simple supply-demand equation, involving one key factor — banks are under pressure from APRA to reduce exposure to residential development lending. If you’re interested you can read more about this here:

https://www.afr.com/property/apra-warns-banks-on-residential-development-20170307-gusahw

The non-bank finance sector in Australia is still relatively small by global standards. However Freehold estimates there is now circa $10 billion invested across Australian real estate debt deals by the non-bank sector. This figure excludes the direct investments by big super funds and the larger offshore funds.

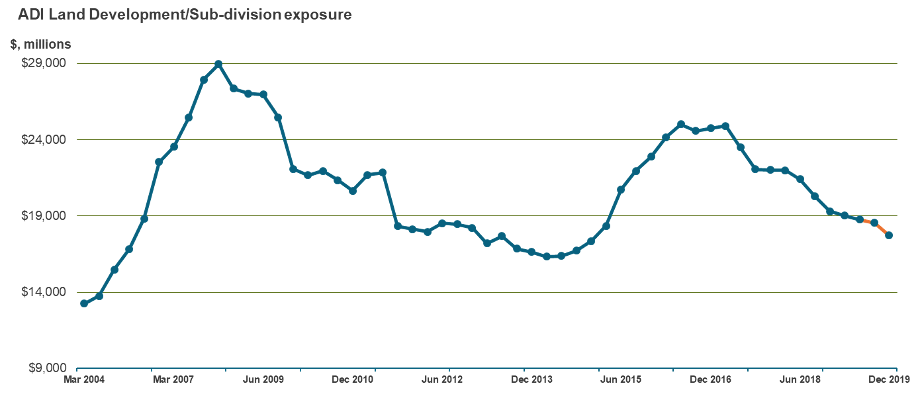

As shown in the chart below, post-GFC, Australian banks reduced their exposure to real estate development but then reverted and steadily increased their exposure from 2013 to December 2016. The impact of the APRA-imposed restrictions on real estate development is evident in the chart from 2017 onwards. This trend is expected to continue through the COVID-19 recovery period.

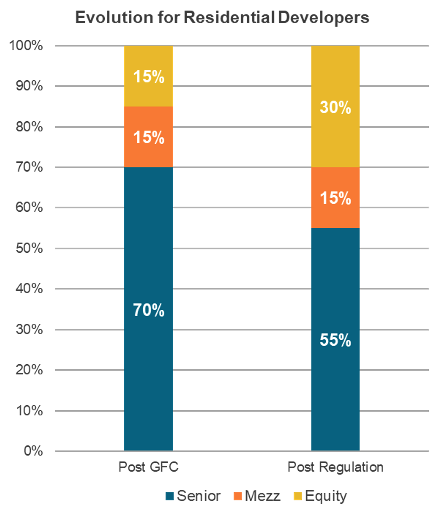

Banks have reduced their exposure to real estate debt primarily by increasing conditions or “hoops” that developers need to jump through to obtain finance. For example, the equity banks require from developers has doubled since APRA-imposed restrictions (see the chart below) in addition to requiring a materially higher pre-sale debt cover on projects.

What are some examples of securities in real estate debt?

Generally speaking, investors have two options when investing. Investors can invest through a unit trust or a debt note. The key difference between the two is that investors in a unit trust receive 100% of the net income the trust generates each financial year. However, the income may fluctuate and the return isn’t fixed.

With a debt note, investors receive a fixed return net of the manager or issuer’s margin. In real estate debt, this margin is usually material and doesn’t provide investors with a transparent look-through on the gross interest or underlying risk taken by investors.

Within real estate debt, the underlying quality of the loans and project sponsors can vary significantly. Freehold segments the market into three buckets, based on the size of the loan or project, as illustrated in the chart below.

In our experience, at the smaller end of the market where loans range between $2m to$7.5m, project sponsors generally lack an institutional grade track record and don’t have the desired management depth. Whereas, at the other end of the spectrum in large $100m plus projects, sponsors have significant track records, governance structures and management depth. However, this end of the market is well-serviced and often doesn’t generate the returns we look for.

Our preferred segment is the mid-market, which is underserviced by the major banks and generally represents institutional-grade opportunities. The key focus for Freehold is quality management teams, sponsor governance and maturity, while also providing superior risk-adjusted returns.

Where does this fit in my portfolio?

We have observed asset allocators place real estate debt in fixed income portfolios as well as real estate portfolios. That said, there is a continued debate about whether real estate debt represents fixed income or simply another form of real estate.

Given this debate, a number of people have written on this subject. The literature takes a couple of different perspectives from looking at the type of debt to what it’s secured against.

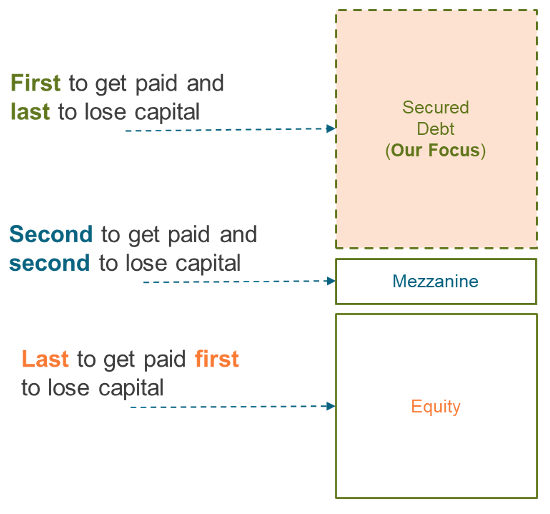

Take for instance Maarten van der Spek. In his 2017 paper in the Journal of Accounting, Finance and Business Studies, van der Spek argues that the key factor is the structure of the debt and the place it sits in the capital stack. He contends that senior secured debt is most akin to fixed income, given investors receive a fixed or floating return that has no correlation with investor outcomes for the equity component or the underlying real estate. Whereas mezzanine is more likely to have investor outcomes correlated to real estate equity, van der Spek further observed that as leverage was increased (to 70%), the correlation to equity and real estate increased marginally and naturally, this would seem the logical outcome of instances where senior debt has less equity buffer in the capital stack.

The flipside to van der Spek’s argument is reasonably straight forward - that the underlying asset is real estate, so it should naturally sit within real estate portfolios.

The tightening of cap rates globally in recent years has seen many institutional investors allocate to real estate debt. Given the late stage of the real estate cycle and low interest rate environment, investors allocated capital to more defensive real estate debt strategies where they were happy to cede equity upside for enhanced income and downside protection.

What is the return profile?

All the return generated from real estate debt is in the form of income. Investors do not receive capital gains.

We target a net return of 7% to 8% a year in the Freehold Debt Income Fund. Pleasingly, the fund has been performing better, delivering an annualised net return of 8.63% from 1 October 2019 to 31 May 2020.

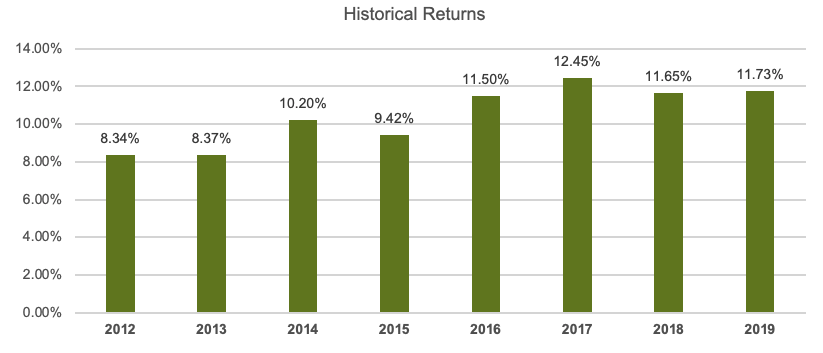

While historically the returns generated by the asset class have been higher (see chart below), recently the increased volume of capital allocated to Australian real estate debt has tightened returns. Our view is that over the medium to long term, they will stabilise in our targeted 7% to 8% a year range.

Returns note:

The returns above represent the consolidated cash flows of Senior Debt SPV’s. SPV cash flows have not been audited. The following assumptions were made in calculating these returns: i) an average of 10% of the fund would be held in bank deposits for cash management purposes, ii) the total fee load applied was approximately similar to the Freehold Debt Income Fund fees. Past performance is not an indicator of future performance.

What is the risk profile?

Senior secured first mortgage debt sits at the top of the capital stack. This means it is the first to get paid and the last to lose capital, should the underlying asset become impaired.

Freehold primarily focuses on senior secure first mortgage debt with conservative LVRs. Where the underlying property becomes impaired, it would have to fall in value by greater than 40% before investors lost any of their principal because our senior debt LVRs generally range between 40% to 60%.

Real estate debt is generally held to maturity, so held at book value. Therefore, investors don’t experience a fluctuation in underlying asset values. Where interest isn’t paid on a monthly basis, it is accrued in the net asset value of the portfolio. The accrued interest is paid to investors when the actual interest or cash is received by the fund.

Conclusion

Over the next 6 to 12 months, Freehold expects there will be less housing stock released into what will be a government-stimulated market. We believe this will be positive for the real estate debt sector, as it should protect capital values and encourage new projects to be brought to market.

Positively, these market dynamics are likely to provide an increased number of opportunities for investors. However, we add a cautionary note here: it will be essential to focus on quality, which (as we’ve noted earlier) can vary significantly across the loans and project sponsors.

This article is sponsored content. The supplier of this content has a commercial arrangement with Switzer Financial Group.