Back on 23 April 2019 I had an article posted on Switzer Daily titled 'Election Day: 18 May 2019'. The editor gave the gist of the article as this: “The intention always was to make May the normal month for our elections. Scott Morrison, therefore, is to be strongly commended for his choice of date.”

Among the points I made about the Australian Constitution was this: “The date of expiry of the terms of senators was set at 30 June in 1910. The intention was to make May the normal month of our elections. Scott Morrison, therefore, is to be strongly commended for his choice of date. Almost every other prime minister, however, has called an early election on that way of measuring the word “early”. The great majority of half-Senate elections have been simultaneous with those of the House of Representatives and held in September, October, November or December of the previous year – meaning a long wait for senators to begin their fixed terms of six years.”

For technical reasons for which I lack the space to explain, the intention back in the first decade of Federation was that the first two elections under the new provisions be in April 1910 and May 1913 – and that is exactly what happened. But then a political crisis arose which produced the double dissolution of 1914. It was followed by a normal House of Representatives plus half-Senate election in May 1917 at which Nationalist prime minister Billy Hughes enjoyed a landslide victory. In 1919 Hughes wanted an early election to stop the growth of the then-emerging Country Party. The next election, therefore, was for the House of Representatives and half the Senate in December 1919. Hughes used the flexibility of the Constitution to get that early election for which the official record gives this justification: “To gain a mandate for post-war reconstruction policies.”

The most frequent type of early election has been the double dissolution to settle disputes between the two houses. There have been seven cases of the use of section 57 of the Constitution: 1914, 1951, 1974, 1975, 1983, 1987 and 2016. The second most frequent use of the early election option has been “To preserve or restore simultaneous elections for the two houses” (six cases, in 1903, 1917, 1955, 1977, 1984 and 1990). By contrast, there have been only three cases in which the prime minister justified his early election by reference to instability in the House of Representatives: 1929, 1931 and 1963.

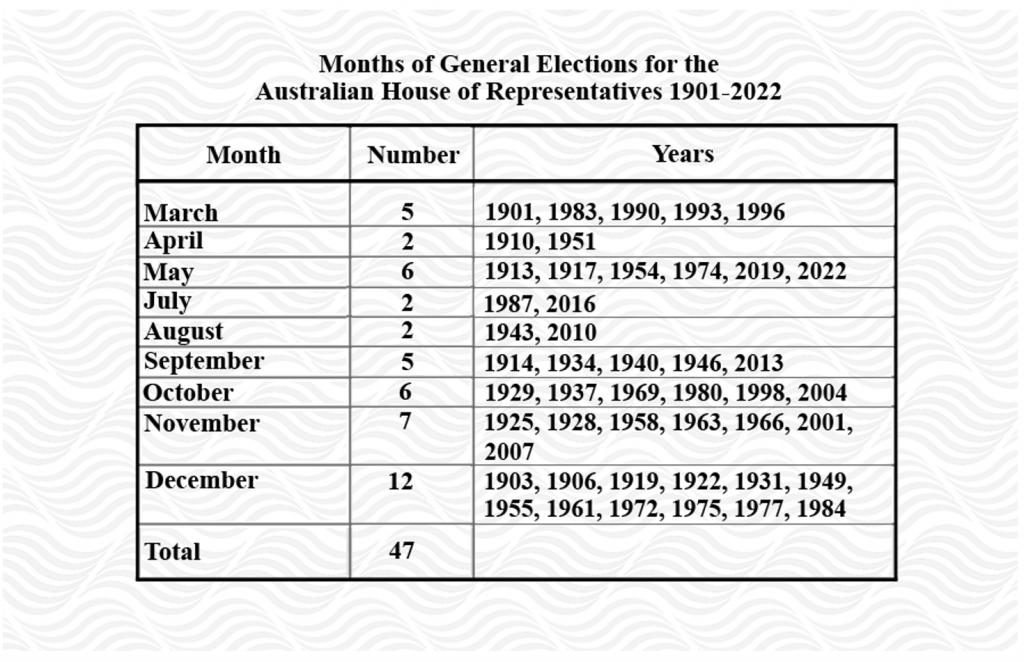

Hughes established a pattern permitted by the Constitution, but not intended by it. That pattern is best demonstrated by the following table:

So, let me now consider the idea of the May election as intended by the Constitution. It applied in 1913 and 1917 – but then Hughes disrupted the pattern and established the idea that Australian elections should take place in the second half of the year (34 cases, compared with only 13 in the first half).

I now consider the six cases of May elections. In 1913, 1917, 2019 and 2022 they were what the Constitution intended: simultaneous elections for House and half-Senate with the terms of senators beginning on 1 July following the election. By contrast, the May 1954 election was for the House of Representatives only while that in May 1974 followed a double dissolution of the two houses pursuant to section 57 of the Constitution. Scott Morrison, therefore, is unique. Not only have his two elections complied with the intention of the Constitution they have been exactly three years apart and held on the equivalent Saturday: 18 May 2019 and 21 May 2022.

During the period when Morrison was making up his mind about the precise election date, there was much commentary to the effect that the present arrangements are unsatisfactory. It became very fashionable to assert that the Constitution be amended to bring about fixed terms of four years. My view is that I support the present arrangements and oppose fixed four-year terms federally. I am aware that all the states/territories have four-year terms which, except for Tasmania, are fixed. That “logic”, however, does not apply at the national level, as I now explain.

The point is that three jurisdictions (Queensland, Northern Territory and ACT) have unicameral parliaments. The other five (New South Wales, Victoria, Western Australia, South Australia and Tasmania) have a Legislative Council but their arrangements are very flexible. By contrast, the Senate’s arrangements are strikingly rigid. That rigidity means the federal politicians understand the idea of fixed eight-year terms for senators is “not on”. The alternative is to elect the entire Senate every four years. The machines of big political parties won’t have a bar of that idea because it would mean admitting to the Senate a host of senators from minor parties, such as the Animal Justice Party, Shooters, Fishers and Farmers etc. The machines of big political parties don’t want too much democracy!

My final point is this: these reformers labour under the idea that prime ministers have consistently abused their power of dissolution. It is a proposition I deny: the power has only been abused very rarely – such as Hughes in December 1919 – but should remain in the hands of the prime minister for reasons of good government.