Whenever a high-profile company lists on the Australian stock market it attracts much excitement. Employees and founders enjoy some financial gains and investors get a chance to invest in a potentially exciting stock.

For these reasons, fast-food chain Guzman Y Gomez was one of the biggest financial events of 2024. It undertook an initial public offering which meant for the first time, its shares were available to the public and started being traded on the stock exchange.

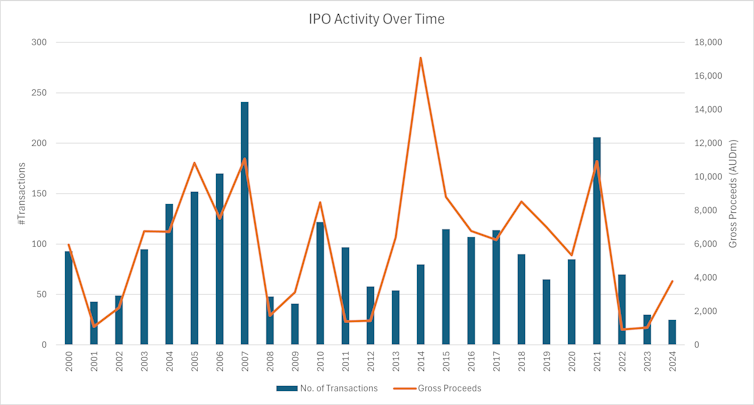

However, such public offerings have become rare with many companies remaining private instead of listing on the market.

Indeed, the number of businesses in Australia listed on the stock exchange is declining. This has been described as the worst public offering drought “since the global financial crisis”.

In response, on Monday, the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC) announced measures to encourage more listings by streamlining the initial public offering process.

Firms undertake an initial public offering by filing documents with ASIC. These includes a “prospectus”, which details the information investors might need to evaluate whether to buy shares.

ASIC reviews the documentation and then decides if changes are necessary or whether to let the business list.

Typically, this requires the business to use an investment bank to manage the process and a law firm to prepare the documentation. The business will also engage an underwriter to evaluate the offering and ensure it raises enough capital. All these services cost money.

When they are trading, the business must comply with additional regulations imposed by ASIC and the Australian Securities Exchange. These include meeting corporate governance, continuous disclosure and other operating requirements.

There are many potential gains for a business and the public to list on the stock exchange.

Companies can encourage employees by paying them with shares in the business. This gives workers buy-in to the company they help to build. This is much easier when it is listed because employees can identify the value of that incentive and sell shares when they choose.

Being listed can also help raise capital. Having shares listed helps the business raise money to expand. In a direct sense, initial public offerings do this by enabling the firm to sell shares directly to the public rather than being restricted to the subset of investors who can invest in unlisted stocks.

In an indirect sense, being publicly listed forces businesses to comply with even more stringent disclosure rules. This can give lenders and investors more confidence in the firm.

Further, because the shares are now readily traded in the market, they can now be more easily used to acquire, or merge with, another company.

The commission believes one of the biggest barriers to listing on the market is the initial documentation and administrative requirements. They believe if they can slash red tape there will be more listings.

The goal is to help them get their documents in order from the beginning, to reduce the potential number of changes that may be needed. ASIC believes it will make the process cheaper and quicker, and enable firms to better time the initial public offerings for periods of strong demand.

The fast track process would only be open to businesses with a market capitalisation of at least A$100 million and firms that had no ASX escrow requirement.

An escrow is a financial and legal agreement designed to protect buyers and sellers in a transaction. An independent third party holds payment for a fee, until everyone fulfils their transaction responsibilities.

ASIC’s plan to reduce red tape will help but there are other barriers to businesses listing on the sharemarket. These include:

This is part of the reason “dual-class” share structures exist in the United States. These give some shareholders supernormal voting rights, enabling them to retain control. Singapore and Hong Kong also offer dual class structures.

Australia doesn’t have a dual-class system, but enabling such structures could make the market more attractive

ASIC has tried to reduce red tape for larger businesses, but the changes don’t go far enough and more work is necessary to address the underlying factors that cause firms to stay private for longer.