The more I read about the Optus 000 outage, the more staggered I become. The outage was bad, but Optus' behaviour (once again) seems worse.

First, a quick disclaimer. Before I graced the halls of Switzer I worked for Telstra in its corporate affairs team for around six years. I came on to run its blog, Telstra Exchange, and left after a round of redundancies finally saw my team reshuffled and reduced. During my time there I worked on crisis management, and I'm proud to have worked with all the folks I did during my time there.

From the Black Saturday bushfires that saw us work through Christmas and New Year's to ensure that the right information was getting to the right people through to countless floods and disasters, cyber preparedness, COVID lockdowns (which exploded the nation's need for data) and even a 000 outage that tragically led to a fatality. I was at the intersection of the company and watched it all unfold from the inside.

While Telstra suffers from legacy issues and a range of bureaucratic hurdles, the people who work there really are top-tier. After spending extensive time with emergency management teams, network teams and even just the people who put the products together, I can say I never met anyone who wanted to do a bad job on purpose.

They're diligent professionals who can be counted on in a crisis. They know their responsibilities - both legally and from a human-standpoint - in a crisis. And more importantly, they act swiftly to ensure people can stay connected. Whether it's for a stupid meme on Instagram or a phone call to 000 that could save a life, keeping the network going and the right people informed is always front-of-mind.

On 18 September, Optus - the nation's second-largest telco - botched a network upgrade. While not unusual - this sort of thing can happen to anyone - the flow-on effects were catastrophic.

The failed network upgrade disrupted access to the Triple Zero (000) emergency call service across South Australia, Western Australia, and the Northern Territory for a staggering 13+ hours.

Three people tragically died during the outage, though the extent to which the lack of access to emergency services directly contributed to each case is the subject of ongoing investigation.

As if it wasn't enough for Optus to flagrantly demonstrate it can't keep your data safe following the so-called "hack" that put the nation's data on display, now questions are being raised about whether it met its regulatory obligation to keep customers safe.

000 isn't a 'nice-to-have'. It's enshrined by law that telcos have to follow certain rules to keep it accessible at all times. Under the Telecommunications Act, it’s Optus’ responsibility to ensure uninterrupted access to the emergency call service. Among those legal requirements are three key issues that Optus completely blew.

Among the legal requirements, Optus needs to:

Failure to do so isn’t just a technical issue or "whoopsie": it’s serious. And the potential legal consequences are serious, too.

It's not just that the issue occurred, however. Sometimes, in a world controlled by a network of complex systems, problems are going to pop up. But it's these three areas identified above that truly staggered me.

Worse still? Optus didn't even detect it themselves.

A routine firewall upgrade conducted at 12:30am triggered the fault that brought down access to Triple Zero. But for more than 13 hours, Optus remained unaware that emergency calls were silently failing in South Australia, Western Australia, and the Northern Territory.

“There was a technical failure in the system and further, there were no alarms to alert us that some emergency calls were not making it through to emergency services.” — Stephen Rue

The first anyone at Optus knew about the outage was when a customer rang the company at 1:30pm. A follow-up alert from South Australian Police came just 20 minutes later.

“We became aware of the severity of the incident when a customer contacted us directly at around one thirty p.m. on Thursday,” CEO Rue told the media

This didn’t appear to be just a monitoring oversight. From the outside, it looked like a fundamental failure of systems design. As Rue admitted, there were no independent alarms to indicate that Triple Zero had stopped working. These alarms are crucial and let central monitoring teams know about faults the second they happen. As Rue tells it, however, the alarm system either failed at the same time as the network routing capability did, or the alarms just weren't configured to detect calls failing to get through to emergency services. Both are as bad as each other.

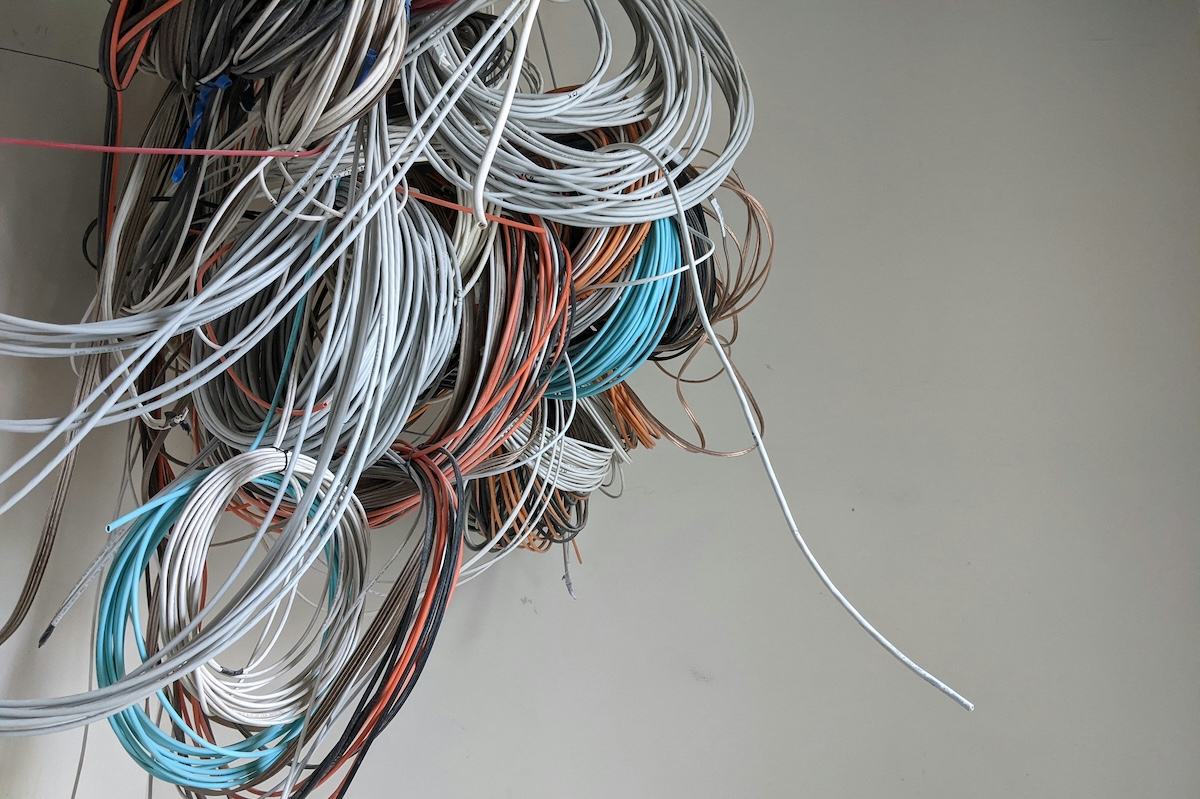

If it's the former, it’s the equivalent of wiring your smoke detector into the same power circuit it’s supposed to alert you about — if the power fails, so does the alarm. The systems designed to monitor Triple Zero traffic should be independent by design, so that when one system fails, the other still works. That didn’t happen here. If it's the latter, it's yet another massive oversight.

Either way, as a result, emergency calls went unanswered for over half a day, and Optus didn’t realise it until the public and police told them.

Even after it found out, however, the failures continued.

The South Australian Premier Peter Malinauskas, gave an interview later in the day about the Optus issues and the subsequent fatalities in his state.

As he tells it, he didn't know there had been an issue, let alone deaths in his state, before Optus CEO Stephen Rue took to the podium to front the media. Nor did the head of the police or the head of emergency services for the state. They all found out via the media.

As the Premier said in a news conference later that day:

Since that [press conference and alert] from Optus, I've spoken to both the Commissioner of Police, Grant Stevens, and the head of the South Australian ambulance service, Rob Elliot. And this is the first they are hearing of this information.

And it only got worse from there as Premier Malinauskas said in a loud and clear voice (emphasis mine, to underscore how wild it is):

I have not witnessed such incompetence from an Australian Corporation in respect to communications. Worse than this, it is somewhat extraordinary to me and senior members of the South Australian government that Optus have seen it fit to make this announcement during the course of a press conference, and then only after the commencement of that press conference to advise senior members of the South Australian government of this occurrence.

I cannot believe that anyone in the senior levels of Optus thought they should craft a media statement and conduct a press conference before advising the South Australian government that they had ascertained two deaths had occurred.

I think, quite frankly, that is reprehensible conduct on behalf of Optus.

The Premier promised nothing short of a shakedown when it came to the investigation it would launch into the issue.

It's worth noting that Stephen Rue has since apologised for this. But we can file it with the rest of the issues here under "too-little, too-late".

Here's what really baffles me though. I understand that Optus is a smaller company than its larger competitors, and that there's a lot to do in a crisis, even when you're well-equipped and fully-staffed. It’s hard to understand how — even in a fast-moving crisis — someone didn’t flag the need to inform emergency services.

Even if the person in the room who manages Optus' relationship with governments (and you don't have to look far to figure out who it is), Stephen Rue isn't new at this. Sure, he's new in the Optus CEO chair, but his last job saw him work hand-in-glove with governments and agencies all over the country running NBN Co. He could have sent a text! Or, if the network didn't allow it, an email? I'd take a carrier pigeon at this stage.

He could have even just turned to his MD for the business and enterprise team, former NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian, who probably could have shared the number for a few people who needed to know about this issue before Stephen Rue fronted the media.

Technology will let us down, people shouldn't

In a world built on systems, sometimes, we have to expect those systems to let us down. But this wasn't just a failure of technology. It’s difficult not to interpret this, from a public perspective, like a failure of people, too.