If you’re reading this in Parliament today, it might be time to stop. Australian government cybersecurity teams have issued a very real warning that a Chinese delegation currently in Parliament House might be taking in more than just the architecture.

Protocol meets paranoia in Parliament

Zhao Leji, one of the most powerful men in the Chinese Communist Party, arrived in Canberra yesterday for high-level talks with Australia’s political leadership. As the current Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, Zhao ranks third in the CCP hierarchy, just below President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Qiang.

His portfolio covers not only legislative matters but also significant influence over the party’s discipline, personnel, and strategic direction, making him one of the chief architects of Beijing’s global engagement and domestic policy.

Zhao’s visit is seen as a diplomatic gesture amid recently thawing relations between Australia and China, after years of trade disputes and mutual suspicion over cyber security and political interference.

The official agenda is wrapped in polite language about “pragmatic cooperation” and “bilateral ties,” but the subtext thanks to Pauline Hanson (as ever) is now about power, security, and influence in the region.

MPs, Senators told to ‘lock down’ their phones

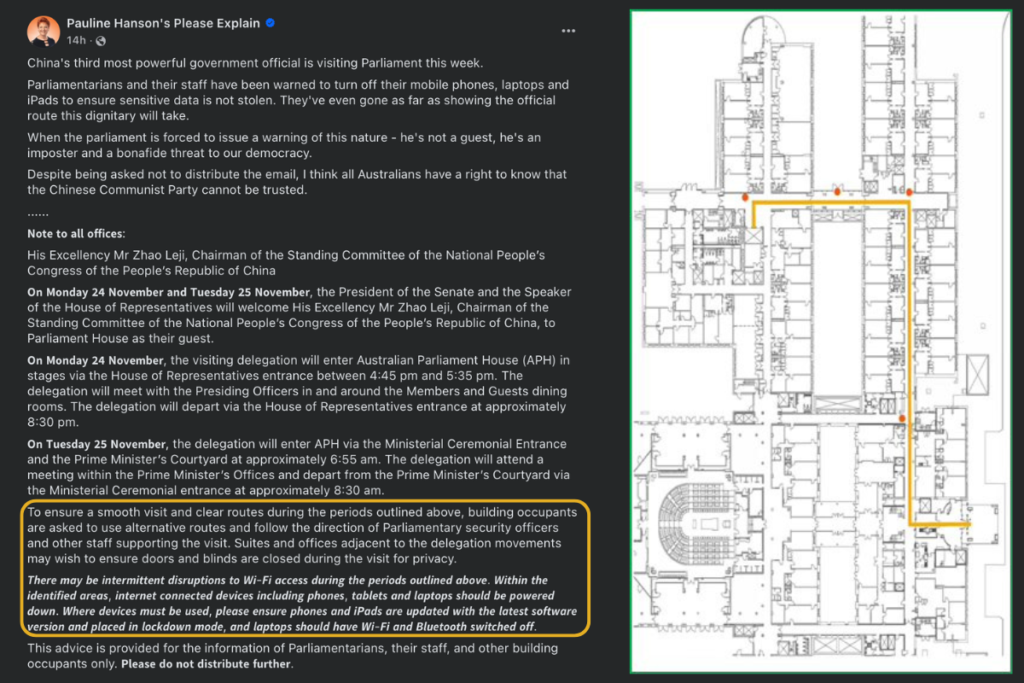

On the eve of Zhao Leji’s high-profile arrival this week, the Department of Parliamentary Services (DPS) sent a memo to all MPs, their staff, and other Parliament House occupants. We know this because, against the advice in the email, prominent race-baiter and unlikely Senator, Pauline Hanson, shared it to her almost 800,000 Facebook followers.

The email laid out the dignitary’s schedule and gave strict instructions about movements in the building, the official route of the delegation, and privacy measures. None of which would be out of place for such a sensitive visit. But it was the paragraph at the bottom that raised eyebrows across the building.

“There may be intermittent disruptions to Wi-Fi access during the periods outlined above,” the DPS wrote.

“Within the identified areas, internet connected devices including phones, tablets and laptops should be powered down. Where devices must be used, please ensure phones and iPads are updated with the latest software version and placed in lockdown mode, and laptops should have Wi-Fi and Bluetooth switched off.”

This isn’t standard procedure for a foreign guest. It is, in fact, classic counter-espionage: the kind of advice that would come from Australia’s intelligence agencies, not building caretakers.

Sound the alarm: Pauline Hanson might be onto something. Ignoring her predictable racially-motivated drivel, the email itself is quite something for security-watchers everywhere.

Even encouraging the use of Apple’s Lockdown Mode should raise eyebrows. This is a mode designed specifically to resist spilling electronic secrets to anyone targeting your devices. It’s designed for diplomats, journalists, or activists at risk from nation-state attackers. When enabled, Lockdown Mode radically restricts the ways your iPhone or iPad can interact with the outside world, sacrificing convenience for maximum protection against sophisticated hacking.

The warning reflects a real and present fear that the Chinese delegation might attempt to intercept wireless signals, access unprotected devices, or conduct signal intelligence collection inside the heart of Australia’s democracy.

China’s history of hacks

China’s ruling Communist Party has a long, well-documented history of conducting cyber espionage against foreign governments, politicians, and even businesspeople. You hear the words “state-sponsored” hackers a lot when it comes to China. That’s how interested in collecting electronic intelligence it is.

For decades, Western security services have warned that any senior Chinese delegation should be assumed to include skilled electronic intelligence operatives, whose job is to vacuum up as much data as possible from wireless networks, Bluetooth signals, unsecured devices, and even physical security lapses.

It has long been observed by intelligence officials and experts that Beijing’s security and foreign affairs doctrine is built on the idea that any information, no matter how benign, could be valuable to Chinese state interests. Whether it’s government negotiations, commercial secrets, or even gossip about internal political divisions, Chinese intelligence agencies have repeatedly targeted parliamentarians, diplomats, and business leaders using sophisticated cyber capabilities.

This is the country, for example, that hacked the New York Times, not because it wanted to do damage. But because it wanted to know the stories it was writing and opted not to publish.

China even has form inside the very building we’re talking about. The Australian Parliament’s own computer systems were compromised by Chinese state-backed hackers in 2019, in an incident that triggered a national security review and mandatory password resets for all MPs and staff.

I’ve spent a lot of my life covering cyber stories and even spent time behind the lines working inside the heart of one of Australia’s largest banks on cyber threats (Which Bank though, you’ll have to guess).

The cyber experts I’ve encountered often say that those travelling through China should take fresh “clean” devices with them that don’t contain any personal or sensitive information as they’ll often be compromised for the secrets they may contain.

And Australia has repeatedly found itself at the sharp end of Chinese political influence tactics many times in recent years, with episodes ranging from soft power diplomacy to outright scandal.

The most notorious case is that of a former Labor senator forced to resign after revelations he’d accepted donations from Chinese-linked businessmen and publicly echoed Beijing’s position on the South China Sea.

Australian Universities, too, have seen controversy: the Chinese government’s has been accused of shaping academic debate and silencing critics on campuses. Meanwhile, there are the repeated cyber attacks on Parliament, hacking of political parties, and foreign interference warnings from intelligence chiefs in Canberra and all over the world.

So as Zhao Leji moves through the halls of Parliament today, there may be a few nervous officials swiftly Googling how to lock down their devices. In case you’re wondering, by the way, here’s how you do it.

You’re welcome.